Heavenly Purgatories: The Postmodern Labyrinth

An interpretation of the Backrooms meme and some corresponding media

In the vein of something readers might find on a site like Geoff Manaugh’s BLDG BLOG, I wanted to provide a bit of personal commentary on material stemming from — and possibly anticipating — the Backrooms meme. This meme has only formally existed for less than five years. So potent are its imagery and narrative possibilities, though, that it’s easy to imagine it enjoying a popularity within a general cultural consciousness rivaling that of the Slender Man. Coincidentally, during the writing of this piece, it was announced that a Backrooms movie has begun production.

As far as I’m aware, the Backrooms has found its most significant outlet through the work of Kane Parsons, also known on YouTube as Kane Pixels, who started making fictional “documentaries” involving the Backrooms a couple of years ago, and who has been named as the aforementioned movie’s director (or co-director). The first of these videos currently boasts 55 million views and almost ninety-thousand comments. As someone who’s only seen maybe a single episode of the show Stranger Things, and knows barely anything of it outside of that, I have the impression that Parsons might be doing something narratively comparable.

Stripped of all narrative elaborations, it’s clear that the Backrooms can be placed, at least initially, in the context of “uncomfortable” imagery of interior spaces. Responses to such imagery often involve claims that one feels dislocated yet aware of a vaguely familiar aspect. A tension between accommodating and hostile design threatens to explode or compress, hanging in the air like a hum. Some grotesque event may be on the verge of happening. This is the very opposite of feng shui.

A variety of videos on YouTube illustrate this sensibility, such as “Uncomfortably familiar Childhood places but it’s sad and nostalgic (Liminal Space)”, “strangely familiar places with unnerving music”, and “places you’ve seen in your dreams.” The description of liminality is hardly new, but it has, I think, been newly applied to characterize these sites, the attributes of which exceed the stricter categories of subway stations or airports. Other terms have been invented, such as “dreamcore” — also the name of a videogame currently in development. The very method of (accidentally) entering the Backrooms reinforces its liminality a bit more literally: one falls through the world, but not out onto the other side, as it were.

Given my own emphases — obvious to anyone who’s followed my work for some time — what interests me most here are the architectural resonances, implicative and historical. For just as I’ve been long concerned with what appears to make architecture work, I’ve also been concerned with its corruptions or vulgarizations; how its morphology may be distorted, or its overall effect rendered as weird, even disconcerting. See, for example, how Roman classicism was distorted by the 18th-century architect Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer, whose moulding profiles for cornices exhibit undulating sequences so seductive, so luscious, as to be fantasies in themselves, separate from the spaces they accentuate.

More recently than that, we might think of the “Victorian” catalogue, made up of items like the gingerbread house and painted lady. For myself, many of the details defining this catalogue continue to offend in a way which I can only describe as aesthetic irritation — the sense that nothing quite comes together; that the building is like a word one knows, yet suddenly cannot recall, and must be substituted with an inadequate synonym — such as the flat-sided arch, the combination of a curved intrados with a pointed-arch extrados, or the cloying, arbitrary fussiness around planar incisions. All of these elements strike me as distortions deriving from a profession awash in self-doubt and clientele mistaking bad taste for originality.

Taste aside, however, distortions such as these, and the countless others populating the majority of the international historical landscape, have been consistently relative. That is, the distortions register because they are set against norms — regardless of whether or not these distortions come to form their own norm: look at, for example, whatever historians cluster under the title of “Baroque.” With the arrival of the 20th century, I think that one of the shifts we begin to see among architecture is that failure (whether that of incompetence or neglect) becomes — potentially and actually — more upsetting than ever before, and harder to typologically situate; and “distortion” often ceases to be the proper descriptive category.

Consider Liberace’s Las Vegas mansion. One of its rooms, photographed below, asks for a comparison to a French rococo chamber, a fitting room, an office space, a cafeteria, and a fashion store. Compare it to the photograph taken of a former high-end store in Boston. None of these resemblances stands out more than another. It’s certainly possible to be in spaces which are aesthetically indeterminate and to not feel disregulated, but the picture here hits me as disturbing for reasons exceeding the array of mirrors or the absence of furnishings. Everything just seems fundamentally wrong. The room is something and nothing, neither alive nor dead: a zombie.

Again, this quality, this zombie-like state, isn’t uncommon. It applies as much to the odd apartment as it does to the odd mansion. A casual look on Zillow around a random city or town plainly reveals this. Once upon a time, I very nearly moved into a basement bedroom where the windows were slits near the tops of the walls, hindering both sunlight and escapees from a house fire, the ceiling was a foot from my head, and the floor was covered by stiff, stained carpeting. Any monthly rent would be too high for these places. It’s amazing to realize that a majority of people might be occupying psychically pernicious or outright noxious spaces, and that this doesn’t necessarily have to do with socioeconomic advantages, or lack thereof.

Of course, it’s one thing to live a reality and quite another to experience it vicariously; and humanity has demonstrated that it enjoys bearing witness to misery, to terror, to the destructive and oppressive, provided this is all within the frame of fiction, or at least at a distance from an event, whether that distance is chronological or geographic. Media like Parsons’ series, the image compilation videos, or the Dreamcore videogame, and the attention surrounding each, evince a core idea fascinating people as a nightmare might, drawing them into worlds which allure because they repel. One viewer writes, “As someone who's [sic] greatest fear is dying alone in an inaccessible situation, doesn't like horror, and has a very deep appreciation for storytelling, I've watched this twice now and I cannot get enough.”

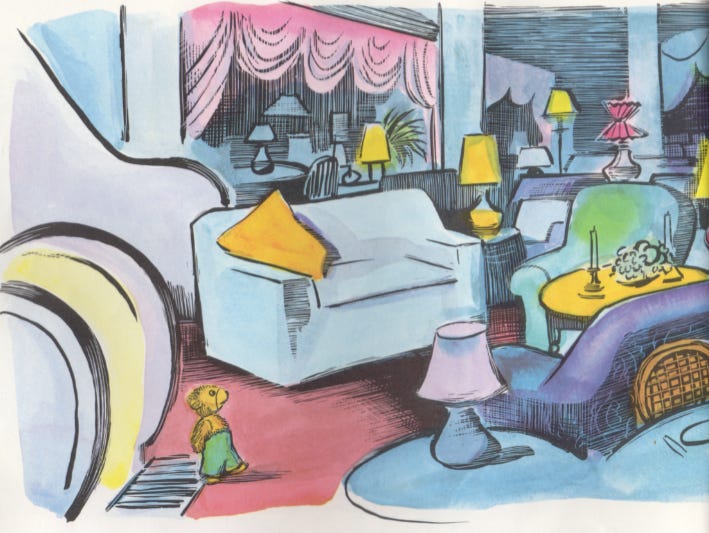

I want to lightly sidestep here for a moment to say that I believe my introduction to the spatially uncanny — albeit a more sedate variety — was by way of the 1968 book Corduroy, written and illustrated by Don Freeman. The book features a department store’s sentient teddy bear who explores the place after-hours, in search of a button for his overalls. Anyone who’s looked through the locked doors or windows of an equivalent store will know what I’m talking about when I say that the store in Corduroy becomes a world removed once the lights go off and the people leave: a maze of things familiar made unfamiliar by abandonment and darkness. Everything has that air of anticipation — yet none of these spaces will ever be occupied in truly domestic fashion, for the domestic aspect derives from the quantity and type of objects, but not their use within that space — even though they’ve been arranged to imply such use. To me, these illustrations summon a nostalgic melancholy, and suggest that a strange kind of hide-and-seek is waiting to be played.

Just to digress for a little longer along a more personal route: during graduate school, I made a series of drawings depicting overhead layouts of imaginary spaces with no definable organizational or aesthetic character. On their own, these pieces aren’t much; but I’m thinking of them as one of those aforementioned resonances with their own associative ripple effect. By their apparent anonymity and labyrinthine design, I find these drawings to be evocative of dungeon crawlers; and I think the Backrooms can be described as a sort of dungeon crawler, too. Compare it to, for instance, the 2017 first-person videogame Dreadhalls (see the video below). Now, however, grim stonework has been replaced by features of modern convenience — features once comprising a vision of a hygienic future; today, symbolic of day job drudgery, or sooner associated with some hallway from a cheap hotel: glaring overhead lights, blank walls and partitions, carpeted floors, and mineral fiber ceiling tiles.

The thing about zombies and budget motels is that both are as fungible as they are transitional — again, neither alive nor dead. The zombie’s identity is a lack of individuality, and this lack is only augmented by the zombie’s usual mass presence. Go to any Motel 6 in the United States and you’ll find pretty much the same thing. Of course, that’s the point. This reliability, this flattening of regional differentiation, and its enforcement by mass quantity, is the basis of the almighty Brand, and its pervasiveness is a quality we’ve internalized since its global establishment. No wonder, then, that the Backrooms and its relations have that potent vibe of familiarity. In a way, the Backrooms is a collective dark fantasy born out of the industrio-consumerist landscape — a landscape where all sorts of mutilative efficiencies and conveniences, funneling back to an altar for a molochian machine god, have deprived so many of our built realms of aesthetic sensitivity.

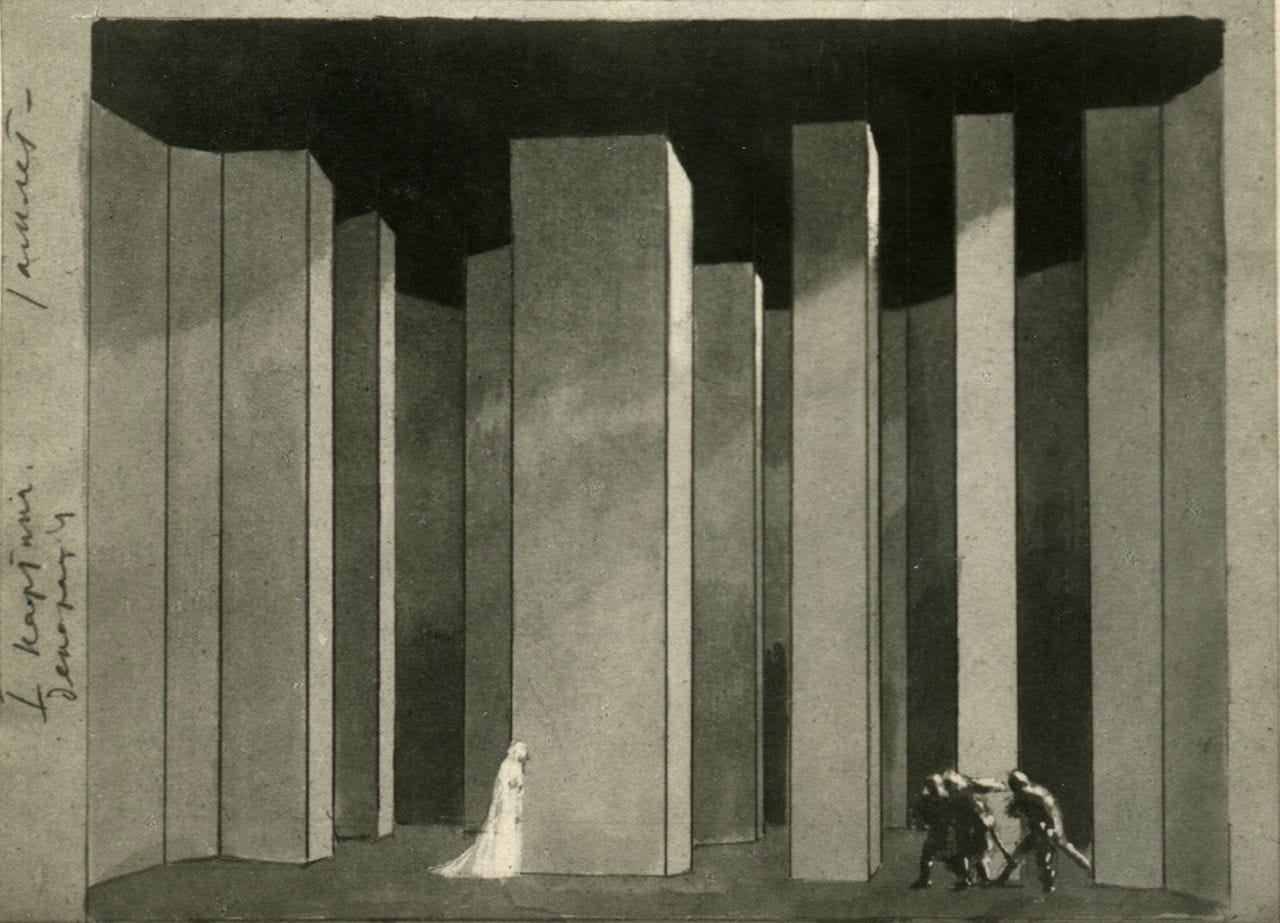

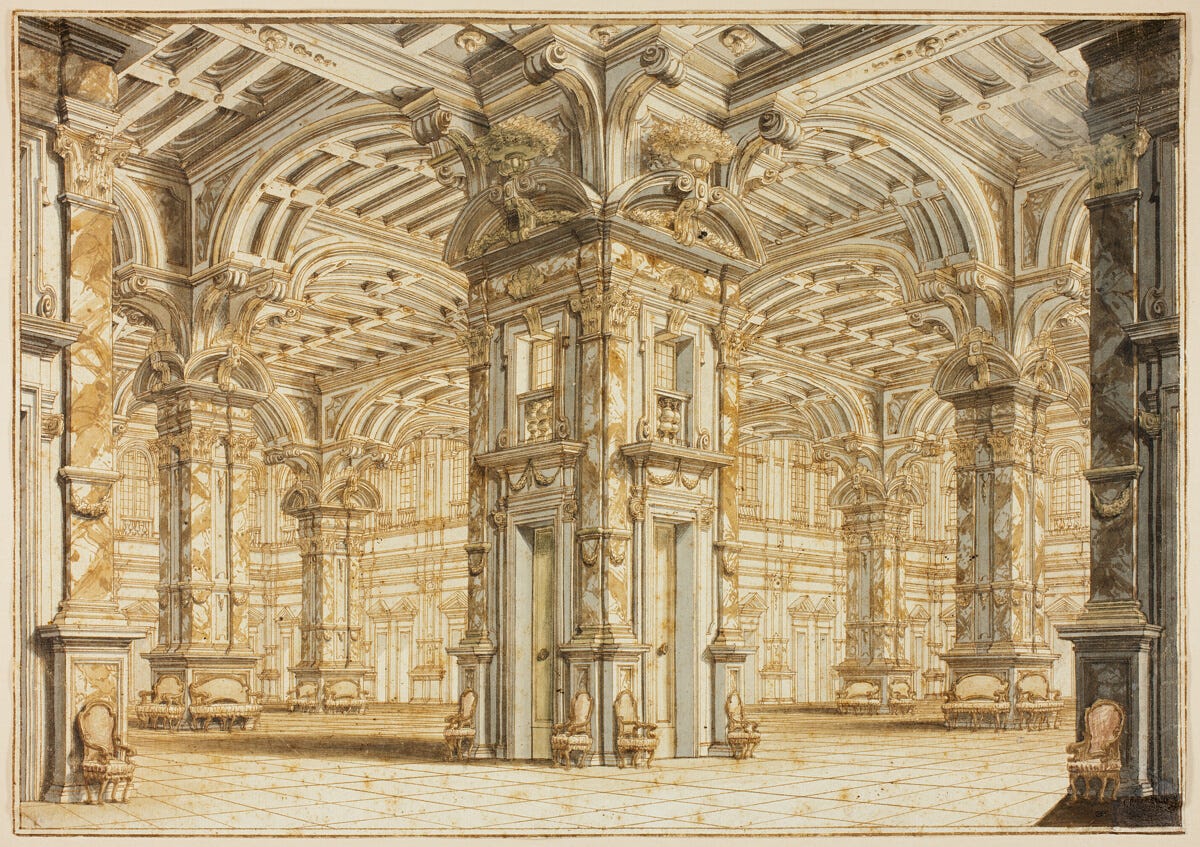

We can travel further back when looking for resonances here, though. In certain respects, the Backrooms recalls a European tradition of stage designs with a focus on architectural perversion, anticipatory feeling, an apparent unending recession of space, or some mixture thereof: for instance, the works produced by Pietro Gonzaga, the Galli da Bibiena family, or — right up to the latter part of the 19th century — Giovanni Zuccarelli. Of course, the presence of Piranesi is unmistakable as well, whose well-known carceri d’invenzione etchings, representing all three of the aforementioned qualities, sit at the center of the capriccio genre. Also relevant are the drawings of Étienne-Louis Boullée: imaginary edifices of a useless vastness and severely limited architectural constituents, as sublime as they are monotonous. And we can again shift ahead, chronologically, to cite the “neutral” theater sets of Edward Gordon Craig, comprised of arrays of sheer-surface blocks.

More anciently, the Backrooms is an iteration of the multicursal labyrinth, most famously known through the story of Theseus and the Minotaur. Far before videogames, subsequent generations would make this mythic formality into entertainment under the anonymously verdant guise of hedge mazes. It’s possible to see later diversions like escape rooms and various haunted attractions as extensions of this theme, too: appreciably different, but not unrelated. Many of us find pleasure, a sublimated masochism, in playing the role of the imprisoned wanderer — so long as there is the promise of escape.

The original title of this article was “Heavenly Nightmares” — but I came to believe that the current title was more exact as it relates to how the Backrooms and its ilk might be positioned among a larger metaphysical framework. Although the idea of purgatory has been variously conceptualized, I associate it with sterile properties.

When we speak of sterility, we’re often making reference to a kind of overly hygienic or antiseptic aspect. For me, this aspect is exemplified by the hip, urban restaurant or cafe that prides itself on a chic conscientiousness of sourcing, production, and distribution — something like the Sweetgreen chain, which asks for an association to so-called environmental awareness by its very name. The irony, I find, is that the interiors of Sweetgreen are strapped for environmental awareness themselves, and instead convey a cold world of efficiency where the pleasure of food, all identically prepared, has been reduced to a set of nutritional values. Sterility can also, quite differently, refer to stuffiness — a lack of ventilation or natural light sources; and I think it’s this quality, suggestive of the subterranean, which the Backrooms has. At the same time, the Backrooms could be taken to be the opposite of sterility. It implies a world which, through inexplicable means, has perpetually generated itself, and may be continuing to go through every conceivable arrangement of its structural resources, far ahead of our ability to keep up with its mutations.

When brought into the fullest possible contemporary context, I think that the Backrooms can’t help but invoke parallel anxieties around artificial intelligence (its publicly unveiled face, anyway) and the multiversal hypothesis. In the case of A.I., a majority of people remains confused about how to describe the form of intelligence on display, if indeed it is intelligence at all. The Backrooms carries a similar ambiguity — one where we are witness to a kind of creativity, but a creativity appearing to lack a specific will of its own, lost among its own algorithmic potential. In the case of of the idea of the multiverse, a speculative extreme postulates a total reality of, to use a recent movie’s title, everything everywhere all at once. The largely unaddressed philosophical problem here is how it becomes possible to justifiably assign meaning to anything if the core attribute of narrative — informational exclusion — does not exist. The Backrooms implants a worry that nothing we are witness to has a teleology, or even a pattern. Architecture is a way of super-adding to the world’s order, but the architecture here may be simply the clothing atop endless absurdity.

In coming around to this article’s end by returning to its title, my thoughts went to when I was first on DeviantArt, a few years after the site’s launch — and all of the media I saw supplementing what was then still a fairly visible goth subculture, like the hundreds of black-and-white photos with vignettes of glum girls standing in cemeteries. Why mention this? Because goth subculture finds a pleasure in proximity to that which is old, dead, and glum; and I think that if we enlarge our scope, we can see how common this kind of anti-pleasure pleasure is, regardless of whether or not formal particulars match up. Usually, it doesn’t come by way of bodily customization, but certainly it’s there just in how we might linger on old and bitter memories, finding a peculiar delectability which we’d prefer to not admit to.

This common desire to craft anxious and melancholic fantasies, to the extent that what began as an aesthetic curiosity develops into a longing — a longing made digestible and permissible through vicariousness: what does this suggest about the humane psyche? Bataille had much to say here. I suppose what’s most and least surprising about the Backrooms is that it is romanticizing a kind of environment few people would ever have expected to be treated as such. Cue that one quote from Brian Eno about desiring the once-undesirable.