After a couple of years of generally writing only critically negative things about Elden Ring — see here and here — the time has come, I guess, to highlight some of its virtues. Given my usual emphases, it also felt right for the focus to be on level design. This will be less of an essay and more of an arbitrarily ordered review of said level design, taken both broadly and minutely, from the suggestive to the concrete. Perhaps contrary to the title, this article isn’t meant to be exhaustive. I simply will be enumerating examples which come to the fore of my mind most obviously.

⋅☆⋅The Carian Study Hall⋅☆⋅

The Carian Study Hall stands as one of Elden Ring’s most imaginatively potent instances of level design, largely because of how very brief it is. Ordinarily a vertically oriented shaft strung with several tiers of walkways and staircases, and accessible only up to a point, the Study Hall inverts its entire structure when a statue is set upon a pedestal in the entry hall, becoming a descent down a capriccio. A trussed network reiterates a perilous motif these games have returned to since Dark Souls’ Anor Londo. Elsewhere, a groin vault is rendered as a regularly undulating floor, each of its crests bound to a column’s capital. Little about the Study Hall poses an actual challenge, aside from an annoying sorcerer. The full effect of the switch-up comes almost entirely out of the new interactive textures arising from how various architectural building blocks are reused, a variety of them usually non-interactive. When Demon’s Souls and Dark Souls were fresher on the scene, Castlevania comparisons were occasionally made, most of these being surface level. One has to wonder, however, if Symphony of the Night’s inverted castle was a point of inspiration for the Study Hall.

⋅☆⋅Divine Tower of Caelid⋅☆⋅

While all of the other Divine Towers in Elden Ring act as gigantic elevator shafts, accessed by a doorway on each’s ground story, the Tower in Caelid uniquely requires navigating around the external structure and its innards, largely oriented around a spoked central superstructure. Like the Carian Study Hall, the Divine Tower of Caelid is a fairly abbreviated obstacle course; and, also like the former, it makes an impression by a pretty simple recontextualizing of architecture. On the outside, broken and unbroken pediments are used as slanted routes from one side of the tower to another as one searches for a point of entry, and the tops of engaged columns serve as miniature camping sites for soldiers, or the foundation for scalable scaffolding. Here, architectural units usually reserved for other uses, practical and symbolic, become the means for a body to move from one spot to the next — one of my favorite design themes from these games. On the inside, Elden Ring takes advantage of its greater allowances for falling great heights and surviving by asking the player to figure out how to go down an enormous space which, according to the in-game world, was never meant to be gone down, to the extent that even a sconce may serve as a platform. After one has figured out the intended path, both externally and internally, the vaguely transgressive fun of repurposing architecture remains.

⋅☆⋅The Wood Near the First Step⋅☆⋅

Despite Elden Ring’s landscape being dotted by thousands of trees, there are, somewhat surprisingly, relatively few woods or forests to be found. Even Liurnia, being primarily composed of a shallow bed of water and innumerable trees, never quite gives the impression of passing through a region of arboreal density. One of these few woods is found not far from one of the game’s earliest checkpoints within a ruined church. A dirt path patrolled by a lone, torch-bearing soldier runs through it. Above the trees, a variety of towering structures beckon prospective eyes. There is, in fact, not much to this wood, although it may feel larger on an initial playthrough. I’ve always enjoyed the distinct sense of enclosure it gives from a view: dozens of gold-topped trees clustering around a singular route, and obscuring their contents with a velvety cloak of shade. To me, it emphasizes a journey’s beginning with perfect lushness, and fondly recalls similarly depicted woodlands from Dragon’s Dogma.

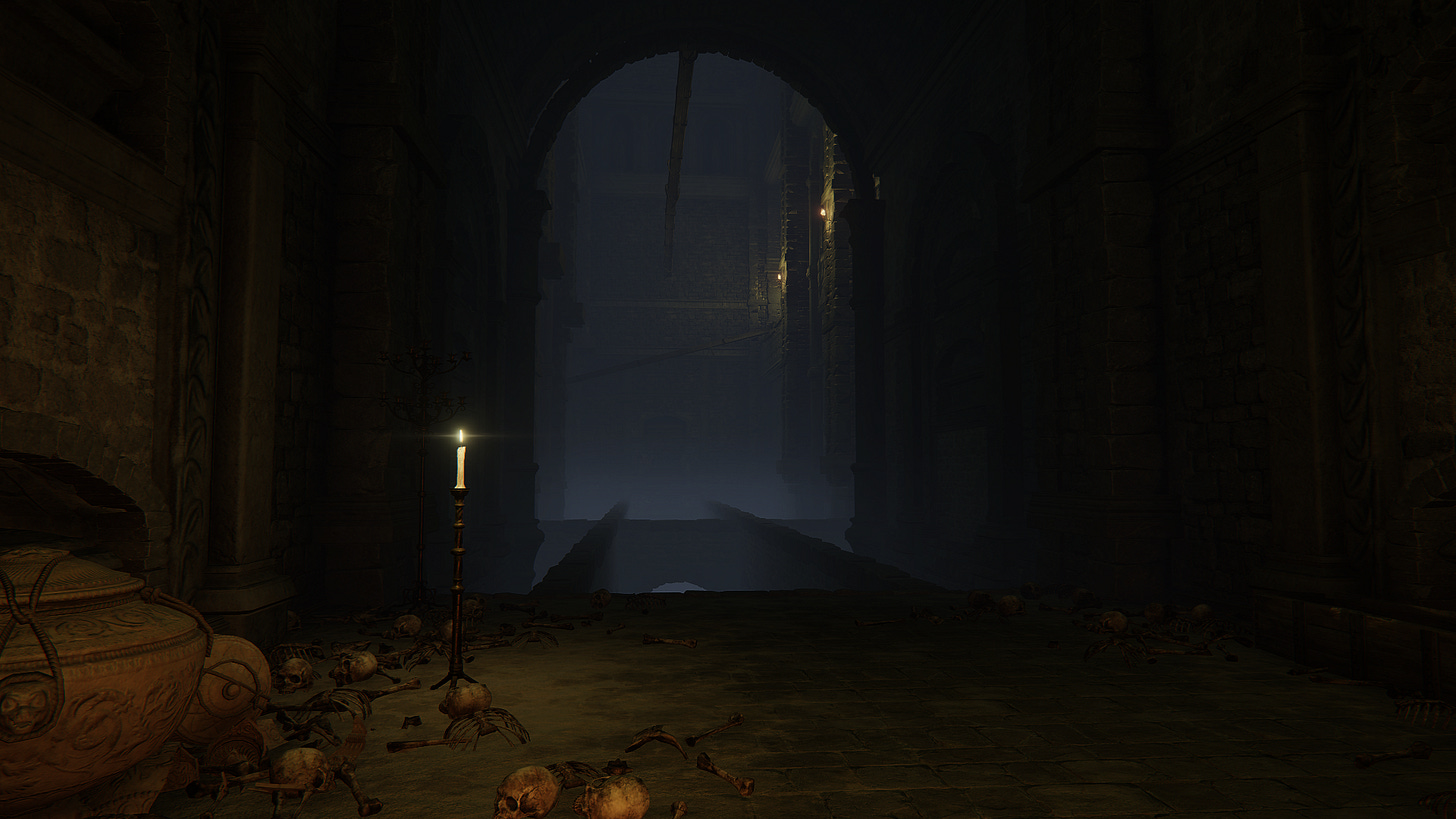

⋅☆⋅Siofra River Well Opening Ruins⋅☆⋅

In a twist, Elden Ring’s Agartha analogue is accessed in an almost disarmingly casual manner, by way of an elevator, the terrestrial hub of which is in plain sight, nestled among a forest on the continent’s southern edge. Compare this to the Great Hollow in Dark Souls, only discoverable by locating an illusory wall behind a treasure chest in one nook within a swamp-ground. It is as if by the time of Elden Ring Miyazaki had come to view this trope — the “secret” world — as one of such eventuality that no attempt was made to obscure its existence. This may also be one consequence of an effort made at accessibility for new players. For myself, this deprived entrance into the underworld of surprise. Nonetheless, what’s first offered gives a particular pleasure to archaeological eyes: a minor sunken classical complex, evoking imagery received of 16th and 17th century Rome, and the cyclopean stonework of more ancient structures. There is an ambience of oldness and yet warmth here unique across all of FromSoftware’s output, reminding me very much of certain paintings by Hubert Robert. Mirroring details of my other choices for this article, access to a higher point in the complex is gained not by staircases but by traversing massive entablatures — a delightful, fleeting moment of architecture activated anew.

⋅☆⋅Various Hero’s Graves⋅☆⋅

Although it’d be hard to argue that any of the major built areas in Elden Ring adhere to a strict real-world practicality, it’s possible to generally play along with the idea that a lot of what we navigate had an original purpose now superimposed upon by the current oppositional occupation. Differently, the Hero’s Graves stand for a kind of — lacking a better term — videogame-y logic that simultaneously evokes for me memories of Sen’s Fortress, from Dark Souls, and the variety of more explicitly nonsensical layouts from Dark Souls 2, where each zone tended to give the impression not of a component of a self-sufficient world, but of a grab-bag obstacle course. The Gelmir Hero’s Grave epitomizes this bizarre sensibility, where you find yourself dashing and ducking into skeleton-occupied alcoves alongside streams of lava, avoiding the patrol of a monstrous chariot, possessed by a strange cocktail of nightmarish trepidation and almost comedic amusement — as if one has been dropped into Hell, only to find that escape is possible so long as one is able to outrun a huge steel ball. Taken as a group, the Hero’s Graves have me pining for a return to a dungeon crawler format like nothing FromSoftware has made since the (apparent) conclusion of both their King’s Field and Shadow Tower series.

⋅☆⋅Lake of Rot⋅☆⋅

It has, for a while now, been a communal meme that Miyazaki both has a penchant for the inclusion of poisonous swamps and ostensibly does so in order to spite a contingent intolerant of this trope. The biggest joke here, perhaps, is that the poisonous aspect of these swamps has rarely been a significant threat. Much more significant is that swamps slow or constrict player movement, leading to the general impression, I suppose, that these areas are a chore, a slog. I happen to enjoy the occasional slog, and continue to regard Dark Souls 2’s Shrine of Amana (not a swamp or poisonous, but largely semi-aquatic, and so limiting both to movement and visibility) as one of that game’s high-points of level design. Similarly, I maintain that what works so well about the swamp from Demon’s Souls is that that extent of its breadth is ambiguous, obscured on all sides by the dark of night and a relentless rain, so that one can imagine it stretching on for miles. A special air of desperation hangs upon the act of entering the place. This is level design of mood, and a kind of chugging monotony is in fact crucial to that mood. In certain respects, Elden Ring’s Lake of Rot feels like a mixture of the Demon Ruins and Lost Izalith from Dark Souls, now put into the context of another poisonous swamp — a swamp where, finally, the poisonous effect is a genuine point of concern. There is at once that infernal explosion of space and the discrete problem of staying the poisonous buildup, while locating tiny islands peppering the zone. A crimson haze hangs in the air as well, visually complicating the charting of a route. If anything, the Lake of Rot could have perhaps been… bigger.

⋅☆⋅Redmane Castle⋅☆⋅

Depending on how early one arrives here during their playthrough, Redmane Castle could be one of the toughest gauntlets. Such was the case for me. In a game where, as I’ve written elsewhere, “[so] many sites of safety and checkpoints can be found, to a point of staggering, map-smothering abundance”, Redmane’s meandering but tightly guarded design recalls those special and tense times from earlier games where, on that initial adventure, and after a dozen failures, you at last barely make it to the lone, and very specifically sited, checkpoint. All of the other forts and minor castles speckling the land considered, none came close to the challenge posed by Redmane; and though challenge is not the element I’m always looking for when I play a FromSoftware title — against their marketing — I’m still game for the occasional brutal maze, much more so than a brutal boss, no matter how slickly designed. Most memorable for me: caught between trying to exit an inner chamber, fending off a couple of aggressive leonine monsters patrolling the inner bailey, and forced to make use of all my relevant resources and the spatial advantages of a choke-point.

⋅☆⋅Crumbling Farum Azula⋅☆⋅

Although Farum Azula very nicely represents a variety of some of FromSoftware’s best traits when it comes to level design, including the aforementioned recontextualizing of architecture — here, displaced and levitating assemblages of domes, columns, piers, and concave walls serve as angled walkways every which way — what I find most impressive about it is how densely packed it is, contrary to its apparent scale on the in-game map; and that this impression of density is firmly retained on subsequent playthroughs. The ruinous yet dizzyingly layered arrangement of the place, which has you wondering about not only where you should go but where you can go, kind of boggles the mind when speculating on how the developers coherently built it up. I would guess that an element of improvisation remained central to the design process.

⋅☆⋅The Branches of Miquella’s Haligtree⋅☆⋅

If I were asked to identify a single defining characteristic of Dark Souls’ level design as compared to its sequels and formal progeny, I think it would be the prioritizing of texture over fidelity. It is still almost unbelievable that areas like Blighttown (indebted to Demon’s Souls), the Tomb of the Giants, or the Great Hollow made it into the final game — not because, as some amount of popular opinion might have it, these are instances of outright bad design, but because they are designs which push the limit of what one would ordinarily expect to sensibly complement the game’s mechanics. Each illustrates Miyazaki and his team striving for a vision, despite accompanying technical wrinkles. In Blighttown, for instance, it was the strain on frame rate, while in the Great Hollow it was the unreliability of footing on irregular surfaces. The introduction to Miquella’s Haligtree, set upon one of the tree’s titantic branches, comes at a time when the mechanics have been so refined, and are now so dependable, that I can’t help but feel some spiky spark of vitality has been lost. More threats stand in your way here than in the Great Hollow, yet it never seems as dangerous as that descent. Still, this doesn’t mean that the Haligtree’s branch isn’t exciting as both a spectacle and a site to figure out. If anything, this is what I’d like more of: places challenging commonsensical notions of what level design is allowed to be, relative to mechanical frameworks and industrial standards of “polish.”

⋅☆⋅Caelid⋅☆⋅

By the broadest stroke possible, I’m including the entirety of Caelid, if only because I think it is atmospherically the most unusual of any Elden Ring location, and the most interesting of the terrestrial regions. Before the game’s release, I withdrew from previewing media concerning it, although on occasion I accidentally saw a screenshot or two. One of these showed an early part of Caelid, with its pungent red sky, swaying ghostly grasses, and the white-gold head of a distant minor Erdtree. It struck me as some dream version of Dark Souls, familiar and freakish, granted entry into the waking world through a slim portal. Caelid is as vivid as it is ugly, blending a wide scene of desolation with a craggy and grotesque organic quality, going well beyond its two-decades-old point of inspiration, The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind. By appearance alone, it compels a generally cautious approach. Huge, cartoonishly disgusting ravens and dogs (reminding me, when I first saw them, of the Mad Wild Dogs from Deadly Premonition) stalk and scout pathways, a blood-red swamp swarmed by dead arboreal appendages boils and bursts, and a crude gateway leads to a town haunted by invisible sorcerers. In a way, Caelid typifies that sort of amplification of gross-out aesthetics so prevalent from the early- to mid-90s, drawing you in like a deadly plant or mushroom might: succulently vivid, but dangerous maybe even to the touch.

꧁────⋆⋅☆⋅⋆────꧂

That’s all — for now, anyway. Elden Ring is large enough that a follow-up to this article, citing other personal highlights, is easily conceivable. If that’s something you’d like to see, let me know. I might get started on it sooner rather than later.

Nice round up! I remember a bunch of these. The tower was easily my favorite. Likewise I was kind of cold on the whole game (too much sprawl) but some of the level design highs make me wonder about what a 10-20 hour fromsoft experience would be like.

The level moment that sticks out for me was the wizard town in caelid near the swamp. For some reason hopping around the roofs there with the absurd number of wizards below was kinda funny.

I frequently return to the fact that little of elden ring sits in my memory especially compared to other fromsouls titles. with the usual cadence of their level design abandoned, I found most moments of the game too-spontaneous and lacking build-up to affect me to the extent that they could have. that said, this created a sort of deadpan effect I appreciated, but perhaps could have been wielded to greater effect–the most obvious example is the fanfareless descent into siofra river valley.

I can't help but reflect on this in the lineage of how fromsouls has always refrained to some degree from telling the player how to think and feel about what they experience, such as how the games are mostly without bgm and without overt plot and dialogue explanations. in that sense, maybe it is a victory of design.

I could see a possibility that this is one of the sentiments behind what people really love about elden ring's open world, as we still live in a time of an overabundance of games that leave little room for the player's own subjectivity. the same, of course, as when dark souls came along. maybe you could say it's a miyazaki-esque metanarrative that the industry keeps idolizing a series whose lessons it repeatedly misunderstands, propping it up for things it never accomplished