The Obfuscating Effect of Contemporary Non-Materialistic Ufology

Historically, ideological divisions within ufology, or groups interested in UFOs, have been divided into, and can still generally be divided into, the materialist, or nuts and bolts, camp and the non-materialist camp. Jerome Clark provides a delineation of his own in his essay, “The Extraterrestrial Hypothesis in the Early UFO Age”, with some alternative terminology and the addition of a third group (which could be slotted under either of the other two groups, depending on the emphases and interpretations):

By the end of the 1960s, the consensus that had guided ufologists through the early years of the UFO controversy had broken down. Though to outsiders ufology was still assumed to be synonymous with belief in visitors from outer space, within ufology three schools of thought had begun to compete for dominance: the materialists (ETH partisans), the occultists (followers of [John] Keel and Jacque Vallée), and the culture commentators (psychosocial theorists), which professed to find existential themes expressed in UFO reports, which were presumed to be subjective experiences.

These camps can be sub-divided into smaller contingents. For example: some materialists might believe that UFOs are all a PsyOp perpetrated by the government; others might believe that they are craft piloted by extraterrestrials from other solar systems. Alternately, while some non-materialists might believe UFOs and ETs to be projections stemming from the human psyche, others might believe that the apparent ETs are closer to cross-cultural conceptualizations of demons, fairies, or ghosts.

However, the words “materialist” and “materialism” — and their antithetical corollaries — break down a little too easily when subjected to a minimum of definitional rigor, and are not necessarily reliable indicators of intellectual content. I, and others, have used “materialist” on occasion to broadly indicate ontologies which treat consciousness as epiphenomenal and which admit only certain forms of phenomena into the spheres of consideration or study. As a consequence, “non-materialist” has often come to be charged with positive, or open-minded, connotations. This is a problematic association within ufology and its attendant discourses if one is to categorize various hypotheses without favoritism.

The main problem for such terms is that we still have no good working definition for what material itself is. Indeed, the very division into the “material” and the “spiritual” by some non-materialists — the idea, for instance, that the soul is materially transcendent, or insubstantial — ironically maintains the materialist, or Cartesian mind/body, paradigm. I will risk overstatement to make a point of this kind of irony, for it appears elsewhere. It is also not fair to uniformly describe advocates for the ETH, or ET hypothesis, as materialists. As I wrote elsewhere:

The ET hypothesis does not rule out paranormal involvement. The mistake, to be clear, is the presumption that, since UFOs and ETs appear to intersect with “supernatural” phenomena, they are supernatural themselves. But this merely reinforces a materialistic framework. Once we accept the possibility that there is no supernatural, but only the natural — aspects of which may be perceived along different lines relating to psycho-biology — , we can also accept the possibility that other beings of an evolutionary range might interact with things beyond our own notions of locality, or materiality.

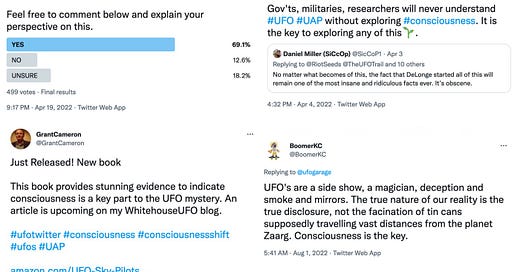

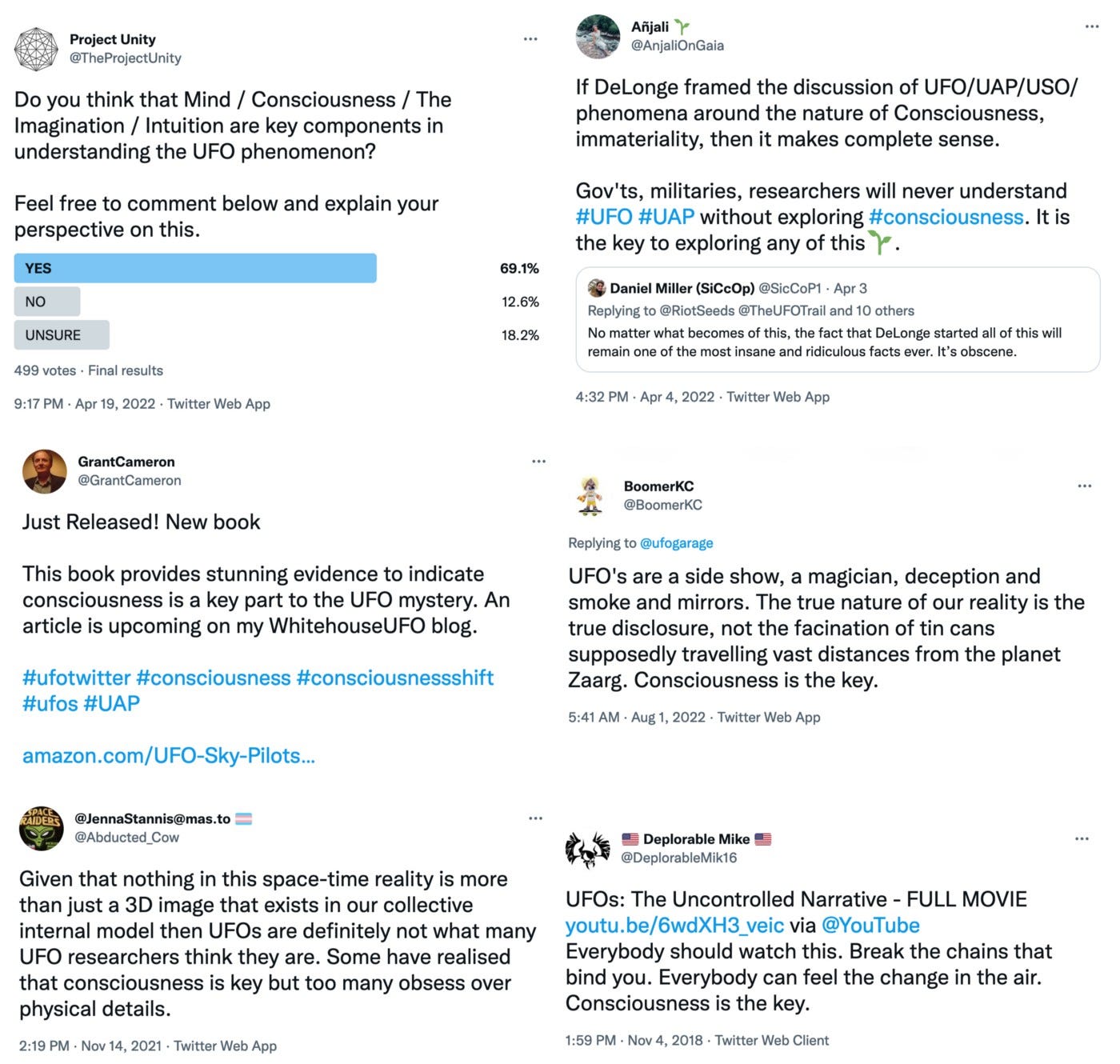

What I’ve been struck by lately, during my observations of and interactions with non-materialist comments and discourses, is this phrase: “The key to UFOs is consciousness.” As this article’s image demonstrates, one can find numerous examples of this phrase, or phrases like it, on social media platforms. It is common enough to have become a refrain, if not also a demographically representative motto. The rationale for this phrase is various. It includes, but is not limited to, studies on the apparent physiological effects of UFOs upon witnesses, the efforts and purported results of figureheads like Steven Greer who advocate a form of “intentional” contact, the practice of remote viewing, as exemplified by Joseph McMoneagle and Ingo Swann, and the act of channeling. These last three factors may be interrelated, since their commonality is the individual’s ability to achieve a type of focused mental state.

But as this insistent phraseology has gained traction, it has escaped commentary on its possession of the same downfall as other popular dogmatic mottos (e.g., “LOVE IS LOVE”, “Everything happens for a reason”, etc.): that is, in its conceptual broadness it approaches the intellectually trivial — and that, by now, it has been repeated with so little clarification that it is in danger of actually obfuscating whatever its intended explanatory power is. This is particularly troubling, given that even non-materialists admit that UFOs’ occupants appear to want everything to be on their terms, and are only too happy to confuse our sense of what is real or truthful.

The increasingly thin separation between the forefront of non-materialist ufology and the word salad of wide-eyed Divine Feminines giddily talking about “consciousness raising” should be a cause of major concern for the field and those looking at it from afar — not because analyses of UFOs and ETs must, by principle, avoid the strange and conform to a kind of respectability politics, but because New Age ideology has an anti-critical, even passive, perspective built into it (refer here to my second essay on abduction reports, wherein I note that “the anomalousness of the message is proof [to New Age types] of its internal consistency, truth, and wisdom.”).

The irony of an ostensibly non-materialist framework reintroducing and unintentionally supporting materialism appears here again. To say that consciousness is the “key” to understanding a phenomenon is only remarkable if consciousness selectively operates. Were this to be the case, though, consciousness would be epiphenomenal, and not an ever-present condition underlying all intelligent interactions. In other words, the implicit hypothetical here situates the material before consciousness. Thus, if one espouses to be a non-materialist, one should also be prepared to say that any sort of interaction between beings is defined by consciousness. Non-materialists have yet to explain how UFOs and ETs represent something categorically anomalous or novel in relation to mentation, or why the consciousness angle necessarily overrules the integration of a “physicalist” approach.

Why is it not equally true or remarkable that “the key to language is consciousness”, or that “the key to qualia is consciousness”? One can keep going with these sorts of statements — which may be, on some level, accurate! — and still be offering only the most porridge-like of inquiries or assertions because the terms of consciousness, how it phenomenally operates, have not yet been delineated (this is, as an aside, why any announcements of a conscious A.I. are extremely premature: one cannot say something is conscious when one does not yet know what, precisely, consciousness is).

As such, non-materialistic ufology and its discourses seem to be in danger of backtracking to a mysterianist-like stance akin to Carl Jung’s hypothesis, offered by his 1959 book, Flying Saucers : A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Skies — a hypothesis Jung explored courageously, but with an almost complete absence of data aside from clients’ dreams and a handful of centuries-old eyewitness accounts (near the book’s end, Jung briefly remarks upon the objects being picked up by radar).

Without a doubt, Jacques Vallée, now a venerable representative for the idea that UFOs and ETs may not constitute phenomena, but rather a singular phenomenon, should be celebrated for his quality and originality of thought. It is rare to find an author whose work on these subjects not only continues to provoke decades later, but can even have more relevance than before. Yet it is worth wondering if Vallée’s line of thinking, and those who have adopted it to varying extents, may be both led and limited by a subtle form of denial. For all of his apparent rigor and critical distance, Vallée has, on occasion, expressed conceptual preference. As he says in a 1986 interview conducted by the also-estimable Jeffrey Mishlove:

“I think that, from my own point of view, I’m going to be very disappointed if UFOs turn out to be nothing more than visitors from another planet, because I think they could be something much more interesting.”

Back in 1999, Greg Sandow wrote an essay entitled “Who’s Afraid of UFOs?”, interrogating the skepticism of prominent critics of the UFO/ET subject, at one point focusing upon Carl Sagan’s narrow presumptions about the modes and manners of extraterrestrial visitations, and wondering why “someone so obviously smart would think so stupidly. The most likely answer, I think, is that Sagan wants to believe that UFOs aren’t here.”

I want to reorient this interrogation towards non-materialist ufology. The point of my quoting Vallée is not to disagree with him — the latter scenario does strike me as more interesting — but to offer a subsequent question (which I have asked, slightly differently, before): might dogmatic non-materialism be an unacknowledged attempt to escape the more mundane, and yet perhaps more upsetting, consequences of one scenario by holding onto the possibilities and vagaries of the transcendent, the immanent?

When one frames the entirety of a matter under the grandest hood of consciousness — or when one refers to persons not as “eyewitnesses” but as “experiencers” — , there is, I think, an accompanying implicit perennial sensibility. If this stuff has always been happening (with the only differences being time and place), if it’s all a phenomenon, if it’s operating on some mythological level, if the imaginal has phenomenal priority, then the urgency of what is material, immediate, confrontational, can be put to the side and we can luxuriate in talking about the roles of owls in certain kinds of shamanism, or the culturally shared, symbolic preeminence of the circle.

I am afraid that we seem to be heading into a dim situation where ufology’s cutting edge thinkers are increasingly indulging precisely the factors which are, by all appearances, meant to muddy clarity and ward off scrutiny. Despite our possession of decades of consistent testimonial (and tangible) data from abductees — data so consistent that the regular exploration of it can, almost unbelievably, impress tedium — , people are continuing to throw their hands up in a sort of self-satisfying bewilderment, exclaiming, in so many words, “How can we make sense of any of this?”

In another essay, I was careful to note that “[the] most objective part of the proverbial scientific method is that it proclaims an objective. There is never an elimination of investment. Each discovery relates to what questions we are asking, and how we are asking them.” I believe, then, that ufology would benefit from a sustained and remorseless reexamination of how much, and in what ways, the conceptual trajectory of its non-materialist strains could be influenced by the desire for a “better” story.

Such a reexamination might, at least, help to cast light upon a number of the conflations and leaps, moving from similitude to exactitude, partially supporting these strains. For instance: that UFOs and ETs have some apparent interactive adjacency to “paranormal” phenomena has been taken to mean that UFOs and ETs are, somehow, fundamentally “paranormal” themselves. I would stress how the use of the word “paranormal” here, too, creates an ontological binary between normality and abnormality. As Ivan T. Sanderson, writing Invisible Residents, remarked with astute brevity, “[Anything] that exists must be natural.”

If Carl Sagan’s bristling resistance to the possibility of current contact found refuge in a set of highly culturally conditioned notions about the unlikeliness of any planetary civilization locating another, it seems to me that the non-materialist demeaning of the ETH, on the grounds of its narrowness, similarly conforms to notions about what extraterrestrial contact would, or even must, be like — as exemplified when Vallée asserts, in Passport to Magonia and Messengers of Deception, respectively, that the phenomenon is too absurd and has too many landings to be anything less than a sequence of staged performances (one significant oversight of this conceptualization is the distinct possibility that, despite the countless exoplanets within our galaxy, Earth’s organic bounty and variety may be relatively unusual, and, thus, especially desirable to other beings with a multiplicity of needs, abilities, and intentions).

It should go without saying that, just as any other person who is engaging these conversations and debates, I hold no monopoly over the solutions or answers, hypothetical or theoretical. But if non-materialist ufology is to secure a better and more self-critical foundation for its investigative parameters, it may not only have to better define its terms, and the application of those terms, but also contend with the possibility that reality is under no obligation to provide us with the “better” narrative — even when that narrative involves, perhaps, and incredibly, extraterrestrial contact.