What do I dislike most about Everything Everywhere All at Once (E.E.A.A.O.)? Is it that it's another multiverse superhero movie cloaked in slightly different garb? or that it’s the comedic partner to the second Matrix movie, full of wearying, pointless, hand-to-hand combat? Two annoying qualities, sure. But far worse than either is this: that E.E.A.A.O.’s message of meaning rests upon a sort of physicalist humanism, or popular nihilism, insistent that all which may be is reducible to mundane data.

Ostensibly against nihilism, the movie wants to be uplifting in sort of contrarian way — yet it presents a situation where nihilism is the only option. Since meaning is nothing more than a sociocultural creation, any meaning-oriented existence is an exercise in cognitively dissonant self-delusion. “This,” the movie says, “— this wearying, banal mess of the day-to-day — this is all we have; so learn to love it until the absurdity of death gobbles you up!” On what world is this not the most bottle-necked outlook on life imaginable? Sadly, it would appear to be ours.

Years ago, such an absurdist message of socially constructed meaning-making — think of the protagonist in some piece of Japanese media who, faced with the abyss, raises their fist, crying, “Small and pathetic I may be; yet still I choose to fight, for such is my humanity!” — might've resonated with me. Not today. Supposedly expanding its scope to the maximum of imagination, E.E.A.A.O.’s vision, in fact, remains strictly within a narrow, comprehensible range of phenomena. It’s not that the movie acknowledges numinous phenomena and, non-hierarchically incorporating these, renders them not as “supernatural” but simply “natural”: it is that, for the movie, the supernatural, the transcendent, the ineffable, never existed to begin with.

Nihilism I understand not as the rejection of meaning, but as the rejection of meaning as an irreducible and inherent feature of the universe. This is the viewpoint the movie advances. Meaning, in its view, is a human imposition among a cosmos of strictly quantitative aspect. It recalls for me a strange book, A Dweller on Two Planets, wherein one of the protagonists, by himself among the Californian wilderness, slowly has his thoughts “tinged with the dead black shadow of materialism.”

Thus joy and sorrow, and every other emotion, became a form of vibration, akin to sound waves, heat waves, light waves and undulation in general. I saw, in brief, my joy become a mere vibratory thrill of nerve tissue, similar, but more complex, to the throb of a violin string. My grief became a similar pulsation or wave. [. . .] None the less, when all queries were finished, when all were reduced to their ultimates, ever and forever faced me a blank wall, insurmountable, and everything ceased short of God. In my despair I cried: — “There is no God, no immortality, and man differs from the oyster only in having a more complex organization. [. . .] Perhaps I myself am only a complex vibration of atoms, not dyads, but multi-atomic arrangements of matter acted upon by — what? Force, wave force, moving ether. We are but puppets, creatures of uncontrollable circumstances.”

E.E.A.A.O. implies that its antagonist, Jobu Tupaki — the daughter of protagonist Evelyn, but from an alternate universe — is wrong because, mass murder aside, through her scouring of all universes to find an answer to the question, “Wherefore existence?”, and, having not found it, she has crippled her capacity to simply value the mundane “fact” of life. Against this, I posit that Tupaki is wrong because her approach of assembling “everything” for a final proof of meaning is analogical to the big data presumption that meaning eventually arises from pure techno-informational aggregation; or the researcher who forgets, or denies, that science is led foremost by the questions it is (un)willing to ask, and the tools of its age.

Tupaki holds a decidedly materialist point of view. When she cannot find, nor get a direct statement from, the Absolute, she concludes that there is no meaning. To put it another way, the movie critiques Tupaki’s interpretation when the critical focus should rather be on her ideology-methodology. While the protagonist of A Dweller on Two Planets’ second half goes on to be initiated into a greater mystery, surmounting (by just a bit) that great and horrific blank wall of materialism, E.E.A.A.O. symbolizes this wall with Tupaki’s “Everything Bagel” and — leaves it at that.

This Warholian reduction of everything to the sentimentally mundane, as popularly represented today by an entertainer like Ricky Gervais, is one of our more pernicious modern fictions. E.E.A.A.O. is a product of a point in time where our inability to discern a superabundance of meaning means that to make any claim otherwise is to expose oneself as a “solipsist”, as an ambassador of a defunct “woo” worldview. The only superabundance of anything in E.E.A.A.O. is simply that of more stuff: one mundane universe set beside another, and another, and another, etc.

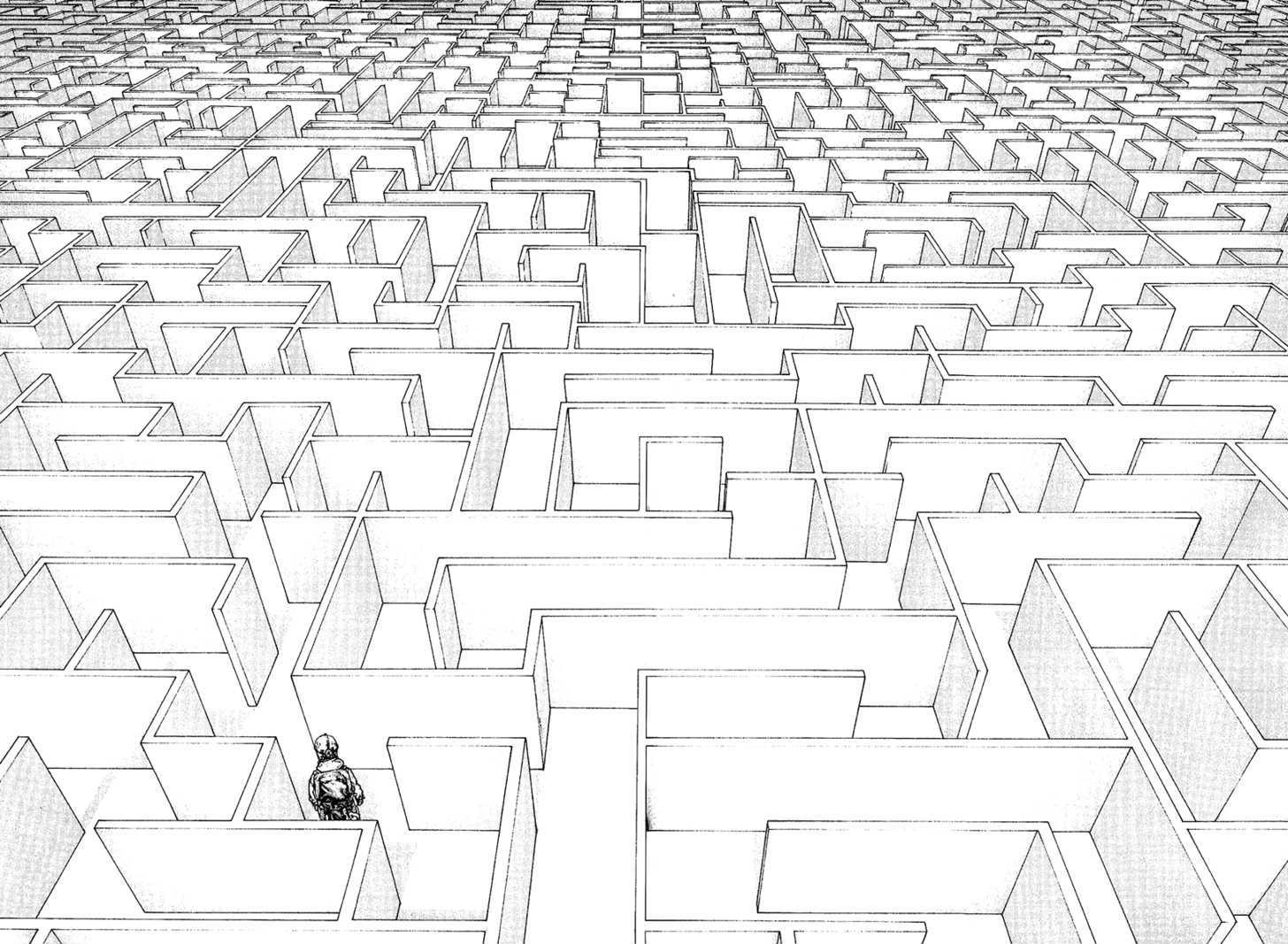

One of the few other universes we’re given a sustained window into seems to be, constitutionally, mostly like our own — except that every human has a series of inadequate hot-dog-like digits for fingers. E.E.A.A.O. propagates a notion of cosmic growth according to an A.I. which has no creative principles, and is merely reassembling various data units in a matrix because it has been programmed to do so. In this sense, the movie replaces a cosmos of mystery with a cosmos of tragedy, recalling Borges’ story, “The Library of Babel.” Since the multiverse operates like a generative A.I. program, the vast majority of universes will be both trivially differentiated and, on some level, dysfunctional.

This implication aligns with the general rationale for the also-popular multiverse theory: that is, given the statistical “unlikelihood” of our universe, scientists and philosophers would rather posit the idea of an infinity of universes, most being statistical failures (as far as harboring organic life is concerned), rather than hypothesize that such “unlikeliness” may be suggestive of singularity — or, even more frighteningly to the materialist, of intentionality. But why is it so ridiculous to imagine something akin to Olaf Stapledon’s visionary book Star Maker, wherein universes come and go sequentially, with the whole of it like an artwork which gains in its glories and complexities upon each reformulation?

As a consequence, E.E.A.A.O.’s message about love as the final recourse of the search for meaning is actually meaningless, for every action herein is categorically never exclusionary, but simply one predetermined result of data playing out all possibilities. Actions are narrative when they are a response excluding other responses — stories are, by definition, exclusive — and so the act of love is narrative too; but when everything is framed as a consequence of probability, with its alternative happening elsewhere, nothing can have that quality of exclusivity, or narrative.

Love becomes just as meaningful, or meaningless, as hate. Why care about victory or loss? Indeed, why care about anything at all? One event or the other happened elsewhere at every conceivable juncture. The atomic bombings of Japan never happened in another one of these universes; big deal that they happened in ours. Nothing obliges us to care except our emotional whims. The supreme absurdity here is personal investment — and nothing is more invested than love.

Should it be misinterpreted, let me say that my critique has nothing to do with the mundane per se, as if I were denying its reality or value, but about how E.E.A.A.O. treats its Everything as so much surface material which can be packed into and objectified as a “bagel,” and that its message unwittingly advocates for the most pathetic, and literally insane, cope imaginable: believing that “Love is the Answer” when it is not sensible to even formulate a question. I have to wonder what about the idea of a meaningful, narrative universe is seen as so unlikely and frightening that a movie depicting its dead-end opposite is hailed as . . . optimistic and meaningful.

As an addendum — a final passage from A Dweller on Two Planets.

You will not think the air any less material, or electricity any less real, because your eyes cannot perceive them. Your eyes are very limited in their visual range; if the One Substance vibrates more or less rapidly than an exceedingly small length of time, producing correspondingly minute force wavelengths, your eyes cannot cognize such vibrations. It is the same with your eyes and hearing. If your eyes and ears were not thus limited, you would see every sound and hear every sunbeam. Every rainbow would be vocal, while heat, which now you only feel, would furnish amazing wealth of sound and vision. [. . .] But so long as you fancy that because you have eyes you can see all that there is to be seen, and that your ears hear all that is worth hearing, so long will you depend on these organs, and gain that sort of false ideas of the Universe which must arise from entire ignorance of all except the tiny bit of creation you occupy. So long, too, will you depend on the telescope to reveal truths about other worlds; you will hunt for evidence of human life on the nearer planets, but you will never find any until you cease to expect that matter will reveal soul; it can not do it, for the finite can not reveal infinity. Turn it about; ask of the soul revealment of itself and of matter also, and all worlds will draw near to you, show their teeming vitality of life, and all nature will uncover such treasures as the hungry soul of science has never found before.

I have to say, I agree with the philosophy you’re expressing, but strongly disagree with your reading of the film. I think the film very explicitly portrays the “bagel” as a mistake, an erroneous and dangerous interpretation of reality. Therefore, it is specifically making the same critique you are. I don’t know how you could come away from the film with the reading that the “bagel” represents the film’s worldview itself. I would have enjoyed more textual evidence for your interpretation, I think you walked right past arguing for the correctness of your own reading and straight into arguing over the philosophy, but I wasn’t convinced that that was even the philosophy on offer from the text. For the record, I had mixed feelings about the film myself (I would have also cut some of the fight scenes), but like I said, I just disagree with your reading of it. I think it was intended (maybe it didn’t succeed) to be a direct refutation of exactly the perspective you ascribe to it.

While I do enjoy E.E.A.A.O. from a storytelling and moviemaking perspective this a very cogent critique of its themes. Very nice.