That Unknown Place to Which I Return

When people speak of their dreams — dreams which they remember, that is — as rare, I find in the statement distance and commonality. For most of my life, dreams have been seemingly scant events, such that the recollection of a few among an entire year might’ve struck me as momentous. Around April of 2020, this began to change. Not only was I having and remembering dreams every two or three days, but the dreams’ vividness, and their symbolic and emotional richness, acquired a new depth.

Usually, we use the term "coincidence" in the sense of an implicit accompanying adverb — “merely” — as if the alignment of certain disparate conditions could only ever be trivial and/or arbitrarily perceived. Against this, I came to conclude that the timing of my personal transformation was linked to the extraordinary consequences of a pandemic: that it was a coincidence in the word's fullest meaning.

After a while, the dreams’ frequency diminished, and it became slightly harder to recall some of the particularities of their details. I think it was sometime early last year when this decrease became most apparent. I now typically recall a couple of dreams a week, provided I allow myself some time after waking to remain in a slightly hypnopompic state and sequence the dream’s contents.

Equally important to that explosion of dreams in early 2020 was my recording them in a journal — which became two, and then three. I now have around two-hundred pages of retained dreams, organized by date and occasionally accompanied by illustrations, mostly to help me better remember a given dream overall.

The intention to remember and record dreams appears to play a part in retention as well, at least for myself; but after a couple of years, my discipline around journaling each dream also diminished. Certain dreams which I regarded as less important have been lost to the psychic ether, and, as I write this today, there is a queue of abbreviated digital notes I still need to transcribe and elaborate on in my handwritten journal. Journaling may sound like a minimal sort of commitment, and in many ways it is! — but a lengthy dream can take thirty to forty minutes to write, and — sometimes I don’t want to wake up and go right into a sustained activity!

What’s been most interesting to me about this record is the opportunity it gives to identify motifs; and what has compelled me to write about any of this is a dream I had on the first of August, 2024. This dream comprises a continuation of a locational motif, a dream-place of ambiguous origin. The first recording I have of it comes from February of 2021. Here is a partial quotation from that entry:

…I am in a very rural area, witnessing gigantic tortoises interact, with the largest of these rearing up on their hind legs in displays of dominance. They can move surprisingly fast, and I notice that this is due to fleshy sacks on the bottoms of their feet which they inflate and then glide on. Behind me I see a distant path, maintained and with less trees. I know this leads to a place, a densely lush valley, from other dreams. I follow that and find myself on the upper end of a grassy hill, near its ridge, with taller, bushier plants covering the other side. I find that I am holding a large frog, and that by my feet is a shallow puddle inhabited by more bullfrogs which do not leap away.

To be clear, the grassy hill mentioned here is not the valley, but a site close to it. The fact that I know the place exists, but find it difficult to precisely locate, suggests that the location has a magical will of its own, only revealing itself upon special occasions. This comes up again in a dream from March of 2023:

I am going along a dirt road in a very rural place. This route is familiar to me — from another dream — and somehow mysterious and dear, precious. In particular, I am trying to find a side path, a trail through flowers and other plants, which leads to a magical-feeling place — a trail I’ve found before — but this time I instead can only find my way to an isolated hill, gotten to by a different trail, with a house or mansion on it. Previously, I believe it was locked, and now I can access parts of it, which are uninhabited and austere, angular.

The third and most recent dream is the one from August, 2024:

I am returning to a place that feels very special, and that I’ve been to before. It’s in a very rural zone, with some sort of large farm house along a dirt road which, if followed far enough, has a trail that goes into lush field with tall grasses and flowers. There is also an immaculate and unoccupied house close to this trail, built close to where the field starts to slope downward. In each dream, I explore a bit more of this place; but that trail is the most intimate feature — almost like a memory of a place from long ago that one yearns to return to.

All told, there appears to be just three dreams having to do with this place which I’ve recorded. Quantitatively, it’s not much to go on, especially since these were not complex or lengthy dreams; yet the emotional depth invoked by this place, which I’ll call the Valley, almost exceeds classification — a sorrow so profound that it is indistinguishable from the greatest joy; as if one could cry beyond the point of having any more tears and still not have exhausted the rapturous depth of this melancholy.

At rare times, this invocation has found a milder parallel within other dreams, such as a few involving flying. For one of these flying dreams, from the end of 2023, I wrote of its emotional quality as “sublimely sad-sweet.” Here, I’ll partially quote an entry (having nothing to do with flying) from November of 2021:

Elsewhere, I have found a bunch of old drawings and illustrated books of my making, which I perhaps made during late high school, or earlier — one book in particular featuring small watercolor landscapes, some snowy, some with buildings. The accompanying narrative text — something to do with a “master’s” journey — is clunky and artificially extended; but I have enormous melancholic fondness for this book and the other work. Its scope and vibrancy dazzle me.

My attention was brought back to the dreams while thinking about a portion of a book I finished this year, and also made recent reference to: A Dweller on Two Planets. The author, Frederik S. Oliver, claimed to have served as a medium for another personality who conveyed at least two of his former lives. Around the book’s middle, this personality, who first goes by Zailm, also speaks of his time in between one incarnation and the next. This occurs in a place, or plane, called the land of Lethe.

I had been forced to seek my psychic plane, and because I was I, and am I, that plane is more or less one of isolation. That is to say, it was peopled with the children of my fancy, my experiences, my hopes, longings, aspirations, and my conceptions of persons, places, and things. No two people see in the same way the same world. […] …the heaven, the devachan, of one person is filled with [their] concepts of life, while that of [their] neighbor on either side — so to speak — is peopled with other peculiar mental properties.

To give one example of what Zailm means: for a time, he is joined by another personality who is distinguished as a “real ego”, as distinct from the subjective reconstruction of a person once known. The author writes: “Sometimes, truly, a night dreamer really goes away with another harmonious soul, the two being real souls on a psychic journey, it being no dream, but a fact.” On this voyage, the two visit the domain of one deceased man, a country bearing “some resemblance to the land of Japan, and indeed we found that we were in the concepts of an American who had resided for many years in Japan ere his entrance to the devachan.” While on Earth, this American had a daughter whom he adored, and so he is accompanied by a substitution, a mental projection, of her, whom he lovingly tends to. Meanwhile, his real daughter, who is not dead, goes about her business on Earth.

To me, it’s a strange picture — bittersweet, if not a little depressing — as if the objective-subjective dynamic of Earthly existence has been replaced by an almost totally subjective paradigm, nearing the solipsistic. It would seem to go against the idea that, in the afterlife, our apprehensions became all the more comprehensive. It would also seem to raise the question of whether or not we would desire an idyllic afterlife scenario if we were to know it to be a sort of “fool’s paradise.”

Parenthetically: as I’ve explored some of the literature on reincarnation these past few years, I’ve been further puzzled by near-death experiences (a misnomer, since NDEs do involve death) wherein the individual is greeted by a company of familial and/or friendly faces. If reincarnation is the way of things, then why would the afterlife be so conveniently populated by our closest loved ones? Moreover, why would mediums be able to channel the personalities of individuals who have been long dead?1 The book’s description of the afterlife as a subjectively constructed realm could provide an answer to the first question. It is difficult, though, to not see in this description a strangely tragic picture: the soul’s abandonment to a veil of appearances.

My main interest with the book and its connection to my dreams is its description of the afterlife Zailm finds himself in.

…I seemed to have come into a beautiful valley, hemmed in by azure hued mountains. Before me stood a building of unpretentious exterior. Irregular in its outlines, it seemed to have been built in sections, added as more rooms became necessary. What an altogether excellent idea that was, I thought. It was formed of slabs of rock, not quarried, but naturally scaled from the ledge. In places it was three stories high, in others only two, but mainly all the rooms were on the ground floor. What sort of people lived here? Certainly people whose architectural abandon was after my own heart. I felt, ere seeing them, already friendly. Assuredly they lacked not the love of beauty, for covering the quaintly picturesque dwelling ran perennial vines, while all about lay tasteful gardens. Should I venture to intrude my presence? As I considered, a man opened a door near me and came forward. He had a very familiar appearance; where had I seen him?

Those acquainted with Richard Matheson’s 1978 novel, What Dreams May Come, or (more likely) its 1998 film adaptation, will probably note the parallels between this panorama and Matheson’s conceptualization of an afterlife, including the emergence of a tutelary figure who turns out to be a relation. For Zailm, the person is his father; for Matheson’s character, it is his son. Having not read the book myself, I would like to know if A Dweller on Two Planets is or isn’t counted among its bibliography.

I mention A Dweller on Two Planets and What Dreams May Come (certain characteristic resemblances aside) because my experience of waking from these dreams is the closest I’m able to imagine returning from a NDE and trying to explain it to other people. I’m reminded of Elizabeth Krohn’s attempt at describing the landscape she found herself in after being struck and killed by a bolt of lightning:

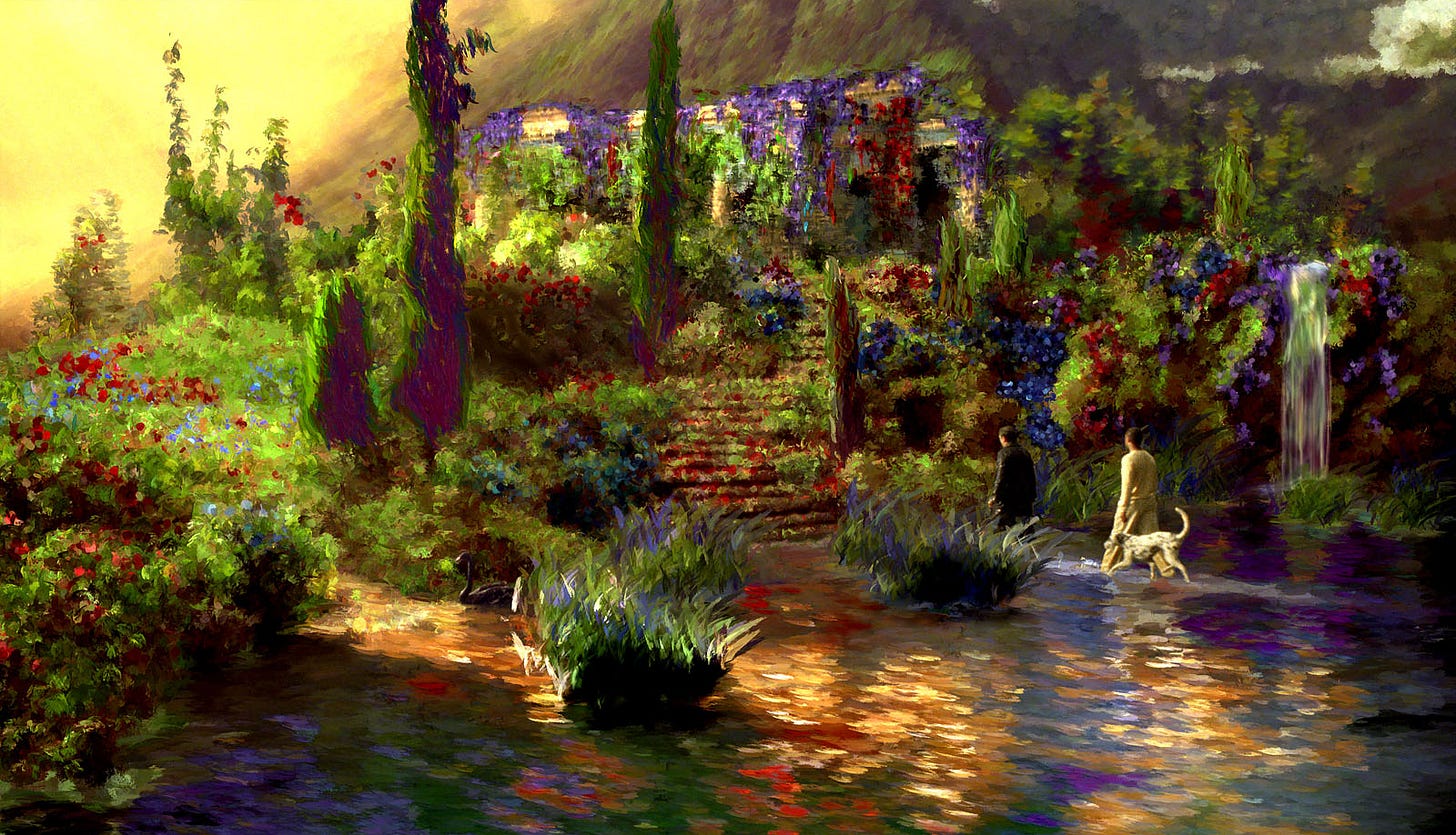

…I call it a garden, but it was not like any garden I’ve seen here. The colors were different. It was like from a different spectrum. I couldn’t even tell you what colors they were. The plants and the flowers were, like, exploding with color; they kept blossoming, and color was just exploding.

Regardless of the minor purpose all writing has of releasing one’s thoughts to an arena of greater clarity, my main communcative goal here is to get readers to think about places from their own dreams — places with a notable level of persistence and/or reality apart from what we might expect of our subjective constructions.

By the latter trait, I mean that many of my preoccupations, thoughtful and creative, have prejudiced me to often consider the afterlife — a personalized afterlife, or at least a kind of psychic refuge — in architectural terms. Now and then, I’ve wondered if various artists of capriccios, such as G. B. Piranesi, Hendrik van Steenwijk II, Rombout van Troyen, or Jean-Jacques Lequeu, came to view their work along the lines of posthumous spaces. What could be more appealing to the obsessive artist of imaginary places than the habitation and exploration of their own fantasies? This line of thinking has also affected my perceptions of certain videogames and their immortal, unchanging locations. I can recall, for instance, having conversations during 2012 which set Dark Souls along the lines of being a type of heaven — one wherein the mysteries and yearning-pangs of existence only deepen.

To be sure, architecture does play a role in my dreams, usually by way of my noticing and dwelling on structural details. Still, it surprises me that this place, most special and dear, is not a place so much as an area of vaguely defined territory; and that the architectural aspects are so subsidiary as to be literally marginal.

But, certain books and near-death experiences aside, I suppose it’s not clear why I’m connecting the Valley to the afterlife at all. I’m not sure I can provide an answer to that, aside from having the very personal sense of something like — “Oh! This is what it would, or will, be like to die and come ‘home’.” How one could have that sense without a memory of death and its subsequent events is, of course, another mystery. Perhaps it’s a convergence of clichés, preferences, and the occasional ambiguity of dreams — yet there is that emotional depth which I don’t think can be reduced to a form of culturally contingent sentimentality. To me, it feels as if the Valley has a reality which is tied to my psyche but, also, somehow separate from it.

A month or two ago, I made a short drive to a gas station from my house to get some mediocre gas station coffee and an even more mediocre breakfast sandwich in preparation for my workday. As I was pulling into the station’s parking lot, I was struck by the speculative thought: How dear might any of this mundanity be to one who had been, for one reason or another, removed from it for centuries, if not millennia? Suddenly, I was affected. It was as if, for an instant, I was able to tap into the infinite preciousness of — what? the Earth; something to do with life, experience, perception; the small as set against the large. My eyes watered. The world, right down to the dullest and meanest of details, became valuable beyond the most literate and subtle profusion of words.

I’m recounting this because my impression of the Valley appears to come from a comparable kind of comparison — of spending so much time elsewhere, among among the day-to-day friction of life on Earth, only rarely gaining access to this place that one has known since an immemorial time. As I wrote of the trail: it is “like a memory of a place from long ago that one yearns to return to.”

In our singular lives, we may have occasion to come back to places we grew up among during a stage of our childhood. To me, these tend to be strange experiences. I sense the separation between the life I lived there and the place itself, perhaps changed, perhaps more or less the same. I can point here or there and say, “This is where I played by the river,” or, “This is where I was standing when my grandparents came to visit.” But all of that is now gone — including the person I once was. This interplay of space and time is something I tried to explore (fairly indirectly and circuitously) through a previous essay, “The Ruins of Memory.”

But the strangeness of these experiences is not just about that disparity. I think it also has something to do with how melancholy — at least for myself — tends to be (or maybe always is) experienced by way of rumination, rather than through the event proper. In late-2022, since we were close to it from where we were staying, my wife and I drove to a neighborhood I lived in for a couple of years. Before we arrived, I was anticipating a wave of hard-hitting, nostalgic emotions. But none of that occurred upon our arrival and me walking around my family’s former lot. Only within the space of memory does the melancholy arise; and then it is more for that visit than for the neighborhood as a collective memorial for childhood.

What I’m trying to say is that the melancholy of my Valley dreams does not conform to how I experience melancholy during waking life, which is in a retrospective and controlled fashion; yet that is nonetheless the only word I can use to describe the emotional texture. This is why I cite Krohn’s description of “impossible” colors: the melancholy of the Valley is an “impossible” emotion. It is as if the contemplative nature of melancholy becomes immediate, suffusing the site and my body like a fragrance. Through that immediacy, it births a mysterious, joyful grieving which seems to exist outside the scope of our emotional language.

Perhaps that scope can be exceeded when awake — but only seldom, and by those few mystics who apprehend a fleeting insight, such as Hadewijch or Hildegard von Bingen.

Here are two more memories I’m compelled to share, so vague and slightly constituted that I am not sure if they represent real events or media.

In the one, I’m very young — four years old, maybe — and watching a VHS rented from a library or rental store. It involves a boy and a talking dragon who is his (imaginary?) friend. At some point, the dragon decides, or finds it necessary, to leave the boy. Perhaps, despite his less than substantial nature, the dragon is in danger of being found by adults; or the parting represents a new, yet painful, developmental stage for the boy. There is something to do with a railroad — where the two part? the place where they originally found one another? An early morning; or a sunset. The moment of their friendship’s dissolution is beautifully saddening to me.

In the other, I’m on a stairway’s landing at my family’s apartment in Yarmouth, Maine. I’m aware of a music video on the TV, located on the apartment’s ground story. The music video is a cartoon, animated so that the linework vibrates. It features a man by himself among a bare landscape with a curved horizon. The colors are light and soft. What has struck me is the music: a song with a male vocalist who is singing so gently it seems to nearly be a tremulous whisper. Whatever instrumental component there is is similarly quiet. This is a kind of music which I’ve never before heard, immeasurably tender and ephemeral, so sensitive that it could fall apart at a touch.

Whether by degrees real or totally unreal, these memories resurfaced while I wrote as faint psychic situations resembling the emotional territory of the Valley.

Typically, I keep the content of my dreams between myself and my wife. I’m hesitant to expose any of it to the wider world — not out of fear or shame, but because I believe that there is a secret property to dreams that asks for careful handling. Given their delicacy and implications, these are among the most secret of my dreams. Nevertheless, I thought it was a good time to share them.

Throughout my time rereading The Lord of the Rings (like some other people might do around the later, colder months of the year), and as usual, I’ve noted the disparities of emphases between its books and the trilogy of movies. No matter how much I’ve ever enjoyed the movies — once, as a teenager, I fancied The Return of the King to be the greatest of all movies I’d seen — I’ve always enjoyed the books much more, largely for the space they dedicate to the textures of lore, landscape, and the journeys of the separate parties, as opposed to the movies’ general preference for action and warfare.2

What I’ve especially noticed on this rereading is the motif of dreams; and by dreams I mean not just recapitulations of the items of one’s day, but also presentiments, and the means by which one character’s predicament is communicated to another — such as when Frodo perceives Gandalf’s imprisonment by Saruman. The inclusion of dreams within Tolkien’s narrative is significant enough that I would cite it as a major supportive theme, right alongside poetry and trees; yet it is nowhere to be found among Peter Jackson’s interpretation, and I’ve never heard mention of it when people speak or write of their love for the books. Why? Why this invisibility?

Modernity imposes upon dreams a mighty lack of serious representation. Rather than this being attributable to others sharing a comparable personal policy around tenderness, I believe this lack has almost everything to do with the predominant materialist framework we occupy (perpetuated by psychology just as much as anything else), to say nothing of how our daily habits may affect our ability to reliably enter dreams and retain memories of them. Dreams are rendered as psychical whimsies, the depth of which could only ever be a mistaken consequence of try-hard perception. Lacking a reason to establish a practice around our dreams, we forget them; and, when we do remember and share them, we tend to do so for the sake of light conversational flavor, a laugh: “Look at how wacky and random dreams are!”

One of the through lines here has been the difficulty of expressing the qualities of certain dreams; and I again find it difficult to express the vitality which rises out of the remembrance of one’s dreams . . . the gradual ability to forge a web of resonances and meanings from such visions, to feel connected to the night-side of oneself and realize its substance. The power of modernity’s devaluation is potent enough that I doubt any one essay could convince anyone to reorient; but perhaps this piece can serve as one stimulative spark to be combined with another, and then another, down the road — provided one remains open to the guidance of disruptions.

It may be that mediums rarely channel a dead person, and instead are usually channeling the “idea” of a person which has, since the person’s death, assumed an independent existence; and perhaps certain discarnate spirits gravitate towards these personality-objects and assume them like a mask, playing the role during a channeling session. Could it be that I’m just describing something comparable to an egregore, or tulpa?

With the movie adaptation of The Two Towers, the narrative centerpiece is the Battle of Helm’s Deep: an event which, in the book, is recounted over the mere span of several pages. Outside of that specific example, the movies’ inclination is to create conflict where there otherwise should be none, such as the recharacterization of Faramir, or the animosity between Frodo and Sam as the two are crossing over to Mordor.